#53: Meet The 'Underdog' Founder Who Realized Southeast Asia's Talent Can Rival Silicon Valley

Eng Heng’s story of grit, curiosity, and relentless drive to create impact in Southeast Asia

Welcome to SEAmplified’s newsletter—where we share inspiring stories for youths to explore what’s possible in Southeast Asia!

Reading time: 10 minutes

🔥 Trailblazers

Trailblazers features inspiring young startup founders, social leaders, and cultural mavericks in Southeast Asia.“I don’t think I’m doing well,” says Yeo Eng Heng, co-founder of Kabana, a e-commerce analytics firm for Southeast Asia.

“That’s a misconception from everyone.”

I was surprised to hear this from someone whose company was acquired this August. After all, for many founders, an acquisition signals product-market fit and payoff after years of grinding.

Eng Heng says this stems from his “underdog mentality”, but he wasn’t sure why.

“I was a shotgun kid,” he says, revealing that his parents got married shortly after conceiving him.

“There was some form of stigma against me and my parents, and I disliked the way that people were looking at us.” As a child, he witnessed how his parents fought against the stigma, which became a source of motivation for him to work hard to repay them.

Studying in a prestigious primary school, he was one of the few who lived in public housing. Classmates made fun of his pink wallet. He grew up playing basketball, but was often the smallest player on the court, and had to fight harder to win in any race.

“I think these experiences hone my personality of being different and embracing differences,” he says. But as I learned more about his journey in our one-hour chat, I realized that he’s not just an underdog.

From Unclear Ambitions to Startups

Before becoming an entrepreneur, Eng Heng had no clear idea of what he wanted to do.

While he chose to study Communications & New Media (CNM) at the National University of Singapore (NUS), it was not an informed choice.

“CNM was an accident,” he says, “I wanted to do Sociology because of my ex-partner, but when we broke up, I decided to follow my friends to CNM instead.”

The turning point came in his third year in 2019.

He signed up for NUS Overseas Colleges (NOC)—an overseas entrepreneurship program—in Silicon Valley, home to some of the most prominent tech companies like Apple, Google, and Meta.

He decided to join the NOC program after learning about it from the founders of a company he had previously interned for.

But he admits that he initially wanted to go to Silicon Valley because he was a fan of the Golden State Warriors, an American professional basketball team in San Francisco.

“Looking back, it was not a thoughtful decision,” he quips.

Over in Silicon Valley, Eng Heng joined Kyte—a startup that delivers rental cars to your doorstep—as their first product and growth intern. The company was just starting out, they had zero cars, and he recalls working from 8 am to 11 pm daily with a small team of five people.

“I think what hooked me was the idea of working and figuring out the puzzle together,” he says.

He also found himself wearing multiple hats, from running referral programs to brainstorming strategies to get more new and returning customers, and even delivering cars personally to their users.

His eyes sparkled as he recalled his experience there. “I witnessed how tenacious and crazy the founders can be,” he says. “One of the founders started by renting his own car to a user’s doorstep to sell his idea, but that’s super risky, as it came with a legal risk.”

For him, witnessing these firsthand taught him the importance of being resourceful while taking risks to turn an idea into reality.

Due to Covid-19, he had to leave Silicon Valley at the eighth-month mark and continued to work remotely in Singapore. By the time he completed his one-year internship, he witnessed how the startup expanded from five to 30 team members, zero to 100 cars, and operating from one to three cities in the United States.

While he wanted to extend his time at Kyte, he found himself losing sleep while working on it in Singapore. He then decided to focus on his studies for his final year in university, but was “absolutely bored” within a month.

At this moment, a schoolmate introduced him to HeadsUp, a B2B software-as-a-service (SaaS) startup that helps product-growth companies improve their sales conversion rates. It had been incorporated for just over a month, and he joined as their first product manager after speaking to their founder.

It felt like a deja vu moment for Eng Heng: another early-stage startup, another chance to start from scratch again. But the biggest lesson he took away from HeadsUp was the ability to break down complex concepts into fundamental parts, before reassembling them to solve problems—better known as first-principles thinking.

“I was drawn to how the HeadsUp founder thought of problems that way, and I wanted to understand how that could be applied in the business world,” he adds. He would go on to work at HeadsUp for two years.

Those two experiences finally gave him clarity.

“Previously, I felt like I wanted to do something, but I didn’t know what that looked like,” he says. “But these two experiences gave me the answer. The thing I was looking for was a startup.”

The Pivot That Led To Kabana

After leaving HeadsUp, Eng Heng travelled to Europe for six weeks.

He took the chance to validate some ideas in mind, and quickly realized two things: there was an AI wave coming, and people found SaaS software difficult and troublesome to learn and use.

That formed the basis for the first iteration of Kabana—using AI to teach people to use their software. It gained some traction and caught the attention of Linktr.ee, a link-in-bio tool for companies to consolidate all their social media and internet links on one page.

But they decided to pivot.

“I realized that being a founder is tough and it strains my personal life,” he says. “We had to stay up late as we were doing sales to the US from Singapore, but doing sales was my weakness.”

Eng Heng felt that they had to either move to the US or pivot and sell something for Southeast Asia before scaling to the rest of the world.

“Sitting in Singapore, Southeast Asia is your best bet given [our] proximity to the rest of the region, and there’s a decent market size to capture since we’re too small,” he says.

But he had no understanding of Southeast Asia. This spurred him to start analysing regional opportunities by looking at some of the main sectors, such as FinTech, healthcare, logistics, and e-commerce.

“The market for these sectors here is decently big, there’s government support, there’s venture capital that understands the space, and there’s a decent amount of innovation coming up,” he explains.

After analysing for some time, he realised that Southeast Asia determines some trends in the e-commerce industry, and the various grey areas in regulations meant there was a space for him to explore while being scrappy.

They then noticed that Southeast Asian sellers were selling on various platforms like Shopee, Lazada, and TikTok Shop without a single analytics platform. It was this gap that led to Kabana being born as an e-commerce analytics platform for Southeast Asia.

“We were able to build our platform on top of the three marketplaces, which made it easier to penetrate different countries,” he says. “In fact, our first customers were Malaysians and Filipinos, even though we were targeting Singaporeans in the first place.”

Overcoming Superiority Bias

As Kabana grew across Southeast Asia, Eng Heng found himself confronting the biases that he had against the region and non-tech industries.

“I was ignorant,” he admits. “People would think that Westerners are the best in tech, and being able to work in Silicon Valley meant that I’m better than non-tech people and even Southeast Asians.”

When Eng Heng interacted with e-commerce merchants from the Philippines, Malaysia, and Thailand, he was blown away by how they had come up with a sophisticated way of thinking to solve problems in the industry. He realized that “good thinking” was not exclusive to Silicon Valley, even if conditions are different in Southeast Asia.

Southeast Asia’s fragmented market also forced him to rethink how to scale across the region more effectively. He noticed that expansion becomes easier when companies can identify a common thread that binds the region together, just like how e-commerce sellers across Southeast Asia rely on the same marketplaces such as Shopee, Lazada, or TikTok Shop.

But he recognized that every country works differently. What works in Singapore rarely maps neatly onto the Philippines or Thailand, and companies can’t simply copy and paste their success from one market to another.

This means that it is unrealistic to go regional from day one. He feels that it is more important to build resilience and grit to scale across a diverse region like Southeast Asia.

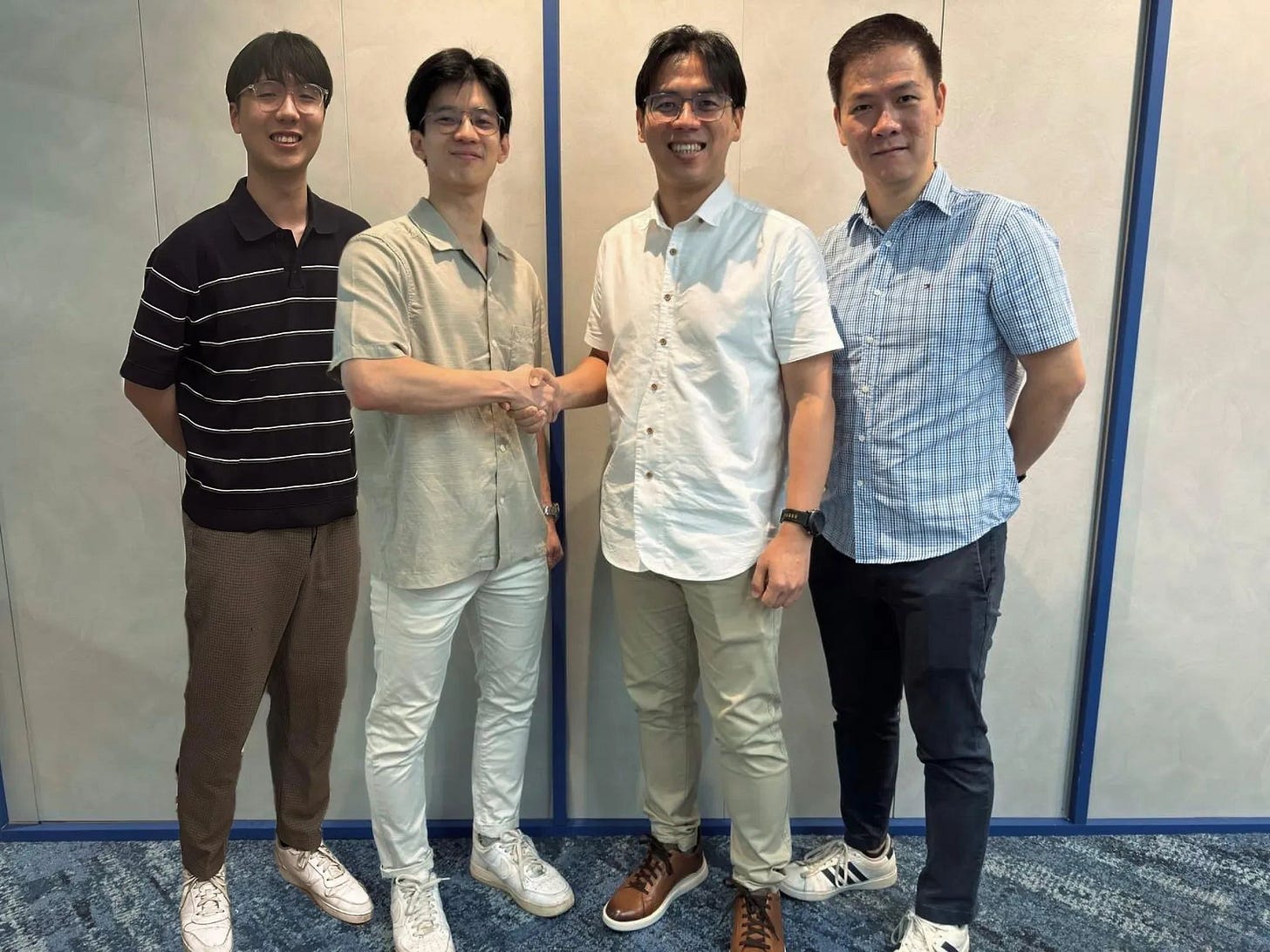

Eng Heng might not know this, but I thought that the groundwork that he laid strengthened Kabana’s foundations, which paved the way for the startup’s acquisition by Revenue Scaler.

When I asked if the acquisition was a surprise to him, he immediately said ‘no’, although he wasn’t sure why.

“I think it’s partly because, when you start doing a tech startup in Southeast Asia, a lot of non-tech companies would reach out and ask if we wanted to consider a joint venture or getting acquired,” he reveals.

Today, Eng Heng continues to serve as an advisor to Kabana. He provides advice on product development and the development of AI features, and helps with product marketing for both Kabana and other portfolio companies in Revenue Scaler.

Venturing Beyond Tech

But Eng Heng is not resting on his laurels.

In a personal Substack post last year, he hinted at the possibility of starting a non-tech business if he’s not working on Kabana.

When Kabana was sold, Eng Heng began to reach out to over 50 non-tech businesses over a few weeks. One thing that surprised him was that many non-tech founders had zero experience in what they’re doing.

For instance, he met a lady who started a company to freeze-dry breast milk, but she had no background in chemistry or biology. He also spoke to founders in Vietnam who built multiple businesses—from schools to a chemical washing plant—but they are not funded by venture capitalists.

These conversations made him realize that there’s no excuse for anyone not to try starting something new, even if they have no experience. “I also wonder why they started—is it because they saw a problem? Or because they’re passionate about it?”

While he does not have all the answers yet, Eng Heng decided to put himself out of his comfort zone and start two businesses—consulting and cat mesh. The goal is to eventually build a ‘big non-tech company’ with multiple vertical businesses, and he started these two businesses to learn how to run one.

With consulting, he gets to talk to different non-tech business owners to understand their pain points and identify opportunities, while the cat mesh business allows him to learn about supply chains and operations.

I was quite intrigued by his plan and wondered—what drives him?

Eng Heng points to a few factors. He claims to get bored easily, and he wants to satisfy his curiosity. He is being ambitious, and he wants to prove that people can make a huge impact in Singapore. He also wants to take care of his family and do crazy things with crazy friends at the same time.

But above all, I think it ties back to his “underdog mentality”. Eng Heng is not satisfied with the status quo—not in Singapore, not in Southeast Asia, and not in the narrative where the West is superior.

To him, being an ‘underdog’ is not a disadvantage, but as a fuel that pushes him to stay curious, to build from scratch, to take risks, and to prove that impact doesn’t just happen in large, stable markets.

Perhaps that reflects a subtle strength in Eng Heng’s journey—a strength that pushes him to take risks, challenge boundaries, and create new possibilities. And in many ways, it mirrors Southeast Asia itself: a region long seen as an underdog, now rapidly becoming one of the most dynamic and thriving markets in the world.

Enjoyed today’s article? Follow SEAmplified on Instagram, TikTok, and LinkedIn for more exciting and exclusive content, hit the subscribe button, and tell us how we did in the poll below!

Have a new idea or lead for a story, feedback on our work, or just want to say hi? Email us at hello@seamplified.com.

The part about confronting superiority bias really resonated. I've seen alot of founders assume Western markets are automatically more sophisticated, when really its just different constraints that produce diferent solutions. Eng Hengs realization about merchants in the Philippines and Malaysia having sophisticated problem solving approaches is spot on. The pivot from selling to US companies to focusing on Southeast Asia shows a maturity thats rare in early stage founders. Building resilience across fragmented markets isnt glamorous, but its the kind of foundational work that actally matters.