Deep Dive: Indonesia's elections - a new hope for youths?

How seriously are candidates taking the youth vote?

Published every three weeks, SEAmplified’s Deep Dive features longform analysis on a developing event or issue in Southeast Asia.

This edition is part two of our Indonesia 2024 presidential elections analysis. For a full overview of key election details, give part one a read here.

❗In Focus: Indonesia's 2024 Presidential Elections - Part 2On Feb 14th, 2024, more than 200 million Indonesians will vote for their next president. 52% of them are millennials and Gen Zs - individuals at the heart of the country’s “demographic dividend”.

Clearly, winning the youth vote is the key to victory at the polls. Indonesia’s political parties are pulling out all the stops to get young voters on their side:

Some, like the Islamic-focused National Mandate Party, have switched to espousing more secular themes as part of a youth-friendly rebrand.

Others, like the Golkar Party, have recruited politicians popular with youths to lead their campaigns, like former Bandung mayor Ridwan Kamil.

In some cases, politicians have also reinvented their personal brands to appeal to youths. Presidential candidate Prabowo Subianto, for example, has sought to portray himself as a “gemoy” septuagenarian.

But what do Indonesia’s youths really want from their next president?

As Jefferson Ng, an Associate Research Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies shared with us earlier, youths are primarily concerned with corruption and inequity, as well as bread-and-butter issues like quality education and jobs.

Indonesia’s Gen Zs, in particular, feel like they’re missing out on the country’s growth prospects. As IDN’s Indonesia Gen Z Report 2024 highlights, 60% of respondents cited socio-economic inequality as their most prominent concern.

Do Indonesian youths have faith that their country’s leaders can provide an answer? According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, just 1.1% of young voters have expressed an interest in politics.

Will 2024 bring change that Indonesia’s youths desire? We examine three key issues central to youths’ concerns and how the presidential candidates have proposed to address them, and investigate whether these proposals will deliver change as desired.

Tackling corruption and patronage politics

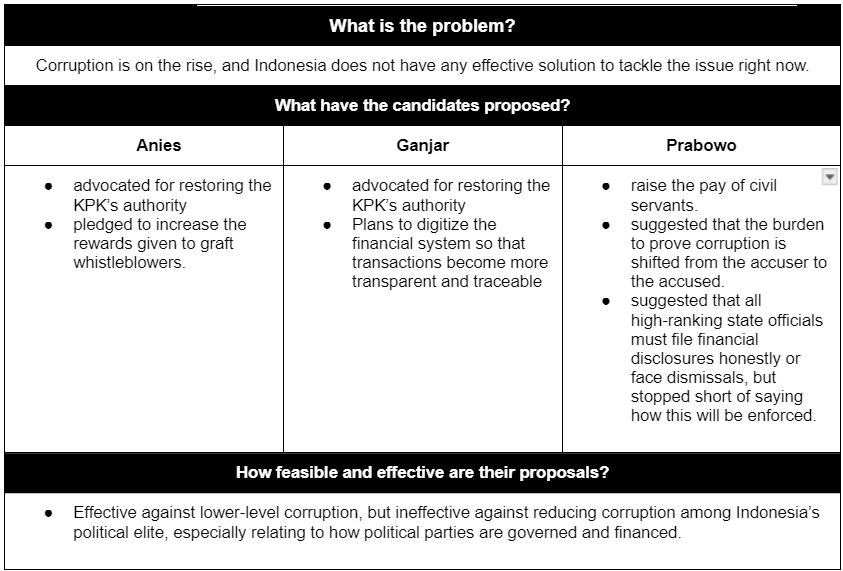

Once considered a shining beacon of anti-corruption, bribery, gratuities, and nepotistic practices in business and politics remain rampant in Indonesia.

Indonesia’s war on corruption saw tremendous progress when incumbent president Joko Widodo first took office in 2014. New measures, like an e-governance system, and an efficient anti-corruption agency, the Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi (KPK), improved the country’s corruption perception index score by six points between 2014 to 2019.

Since 2019 however, Indonesia’s anti-corruption drive seems to have gone awry. A major setback came in the form of an amendment to the KPK Law, which stripped the agency of its autonomy in key investigative functions.

For Indonesia’s youths, corruption and patronage politics not only affects how responsive the country’s political elites are to their needs, but also hurts their economic prospects.

Case in point: Because patronage politics trumps all other concerns, Indonesian electoral candidates are more likely to manage their political campaigns via “tim sukses”, or informal networks, rather than party mechanisms.

Higher corruption is also associated with higher unemployment rates, and higher talent outflows from a country. Some studies also suggest that corruption could even be detrimental to new business creation.

Better, more equal job prospects for all

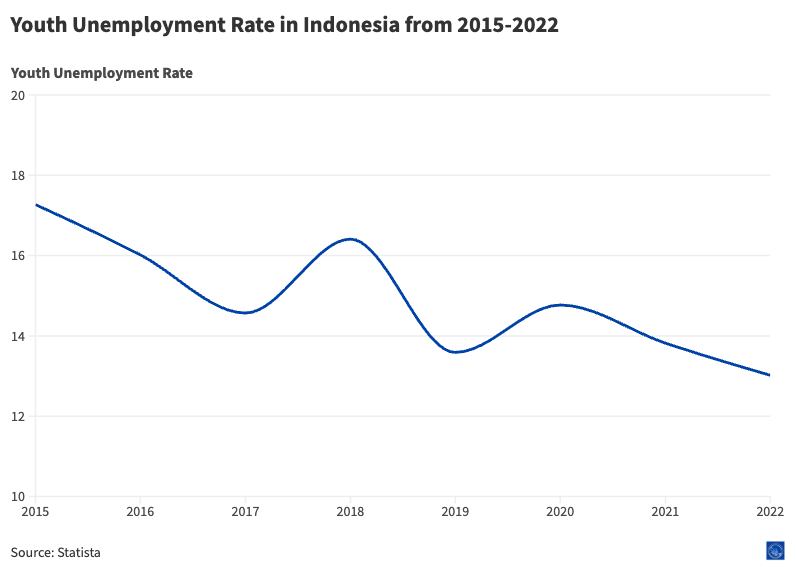

Another key concern among Indonesian youths is jobs. Here, issues like youth unemployment and underemployment and access to education and jobs for rural youths are key concerns.

While Indonesia’s youth unemployment rate has improved over time, it still stands among the highest in Southeast Asia.

The underemployment of Indonesian youths is more pertinent: informally employed youths aged between 15 to 19 years old who are working in non-agricultural sectors grew 8.45% every year between 2015 to 2021.

Indonesia also lags behind in education, with the country placing seventh out of the 10 ASEAN nations in the 2022 ASEAN Youth Development Index.

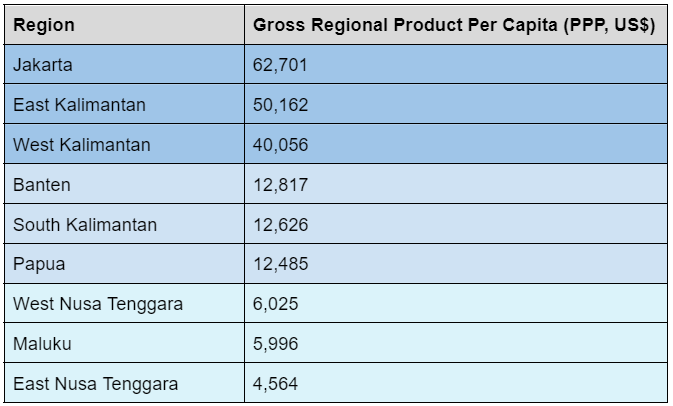

As for access to education and jobs, this is a significant concern especially for youths in rural, less developed regions where incomes remain significantly lower compared to urban centers.

As the table above suggests, there is a wide discrepancy in economic development across Indonesia’s many provinces. But there is also a growing inequality within urban areas, which have seen a spike in their GINI ratios.

On the national level however, Indonesia’s statistics department revealed that the top 20% wealthiest Indonesians contributed nearly 46.7% of the country’s total expenditure in 2022.

A healthier, freer future

It isn’t just the health of Indonesia’s institutions that concern youths: their personal conditions are also at stake.

The data speaks for itself: diabetes cases in Indonesian children skyrocketed 70-fold between 2010 and 2023, with 40% of these cases being in children aged between 10 to 14 years old; Indonesian children also saw the highest cancer diagnosis rates in 2020.

The rise in non-communicable diseases among Indonesia’s youths is alarming and could affect their developmental prospects - and, by extension, Indonesia’s ability to fully leverage its “demographic dividend.”

More worryingly, the country’s new health law, which was passed in August 2023, abolished obligatory healthcare spending. This legal amendment has raised concerns among observers, which warn of potential adverse impacts on fair health outcomes for Indonesians.

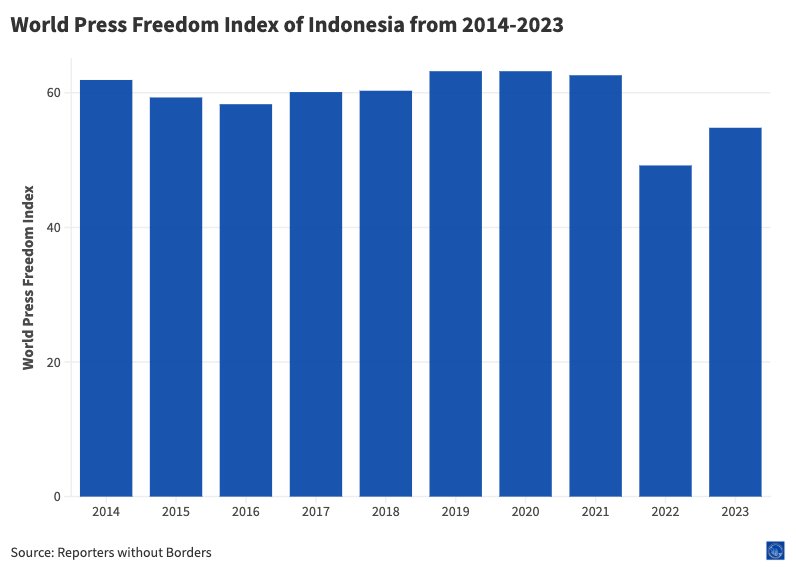

In some sense, Indonesian youths are also concerned with their spiritual health. Freedom of expression was highlighted as a key theme among the country’s educated, young population, and this is especially pertinent when considering Indonesia’s attitude towards press freedom in recent years.

The implications of growing media repression in Indonesia are immense: most Indonesians trust social media as a source of information more than news outlets, and increased government meddling in online public discourse could curtail spaces where youths connect and socialize with each other, as well as restrict access to information that could enable youths to make more informed choices.

Can youth bring real change?

Youths have been a major force in Indonesian politics but, as Professor Diatyka Widya Permata Yasih of Universitas Indonesia writes, the country’s political system has largely failed to address their grievances.

Our analysis shows that the solutions proposed by all three presidential candidates appear to only address youths’ key concerns on a largely superficial level. This suggests that while presidential candidates have acknowledged the importance of the youth vote, how seriously they intend to tackle the issues most pertinent to youths remains questionable.

That begs the question: can Indonesia truly leverage its demographic dividend before it’s too late? The window of opportunity has already run half its course. If the tone of 2024 is anything to go by, it’s easy to understand why Indonesian youths show little interest in their country’s politics.